Civil Contractors NZ Technical Manager Michelle Farrell takes a deep dive into what ‘sustainability’ means, why it matters, and what it might mean for the civil construction industry in New Zealand

It seems right now, the more the word ‘sustainability’ is used, the less it means. Are we talking about United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, reducing carbon emissions or sustaining cashflow on balance sheets? Or is there some universal knowledge we can apply to unpack the buzzword?

First, we need to understand that sustainability is not just about reducing effects on the environment; sustainability can refer to anything: a business, a lifestyle block, a bank account, a country, or an industry. In other words, sustainability can have environmental, economic, social/human and cultural implications. We’re essentially talking about a system, and in this case a sustainable system.

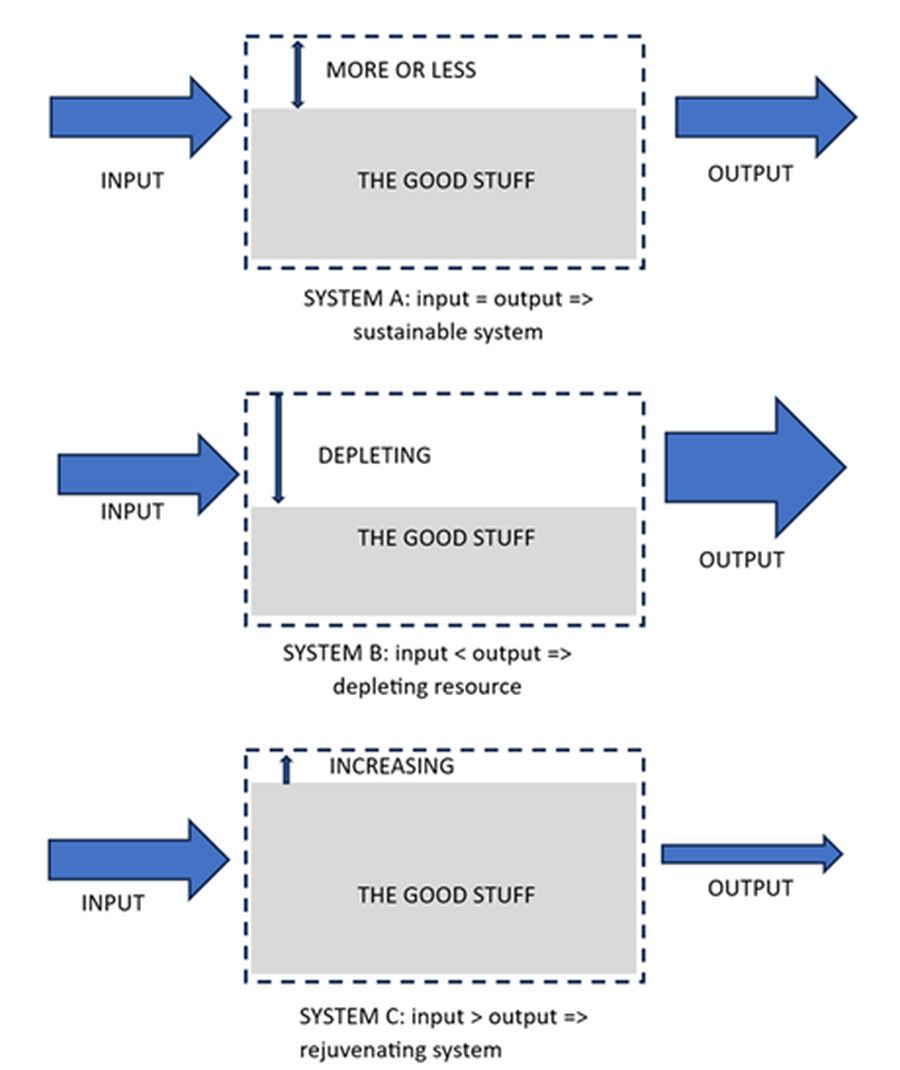

Below are three very simplified system diagrams. System A is sustainable, where the “good stuff” inside our system remains stable; System B is unsustainable, with the good stuff being depleted; and, System C is rejuvenating, where the good stuff is increasing.

It can help to think of a system, in this respect, like a bank account. Provided the money going into a bank account is the same as, or more than, the money going out of the account, the balance inside the account will either stay the same, or increase – this is a sustainable bank account (System A, or System C). Or thinking in terms of human resources in a business – if the number of new employees is less than the number of employees resigning (and the work required remains the same), the business may become unsustainable over time ie the business cannot sustain itself in terms of the human resource, unless the amount of work decreases (System B).

Now let’s apply this thinking to a widget-making business, which very simply uses 100 units of resource to produce 100 units of widgets (System A). If the number of units put in increases to 120, with the same number of output units, then the business may be depleting the good stuff inside – it’s losing too much money, people or other resource, and may be unsustainable. Something needs to be done to bring it back to stable and sustainable, or the business will eventually go bust.

It can get more complicated when we’re trying to understand sustainability in terms of renewable and non-renewable resources though. So, let’s take a look at an example which uses energy to produce a product. Consider a machine which simplistically uses 100 units of energy to produce 100 units of product.

This may seem like a sustainable system – it looks like System A. But let’s momentarily look at the resource being used to produce the 100 units of energy for our machine. If the resource is coal, then the coals’ system is System B (depleting resource), because we are removing coal from the earth far quicker than the earth is making coal (coal is a non-renewable resource). However, if the resource is wind, then the energy system is System A, because wind is a renewable resource and the earth won’t run out of wind.

So, in the case of our machine, when we expand the system boundary to include the energy resource system, the machine is essentially unsustainable when it’s using coal to create the energy in, but is still sustainable when it uses energy from wind.

That’s the reason why the sustainability concept can get confusing – because it depends on where the system boundary (the dotted rectangle) is drawn. We can have what appears to be a sustainable business making widgets, but if we expand the boundary to include the energy resource, it can become an unsustainable system.

We could look at a business’ bank account, which appears sustainable (money in equals money out), but say the business relies on a constant supply of water to make its’ product. Water is a finite resource and if the water supply runs out, the business then becomes unsustainable.

Consider a country as a system, containing many businesses inside its boundary, where we are using sustainable resources inside our system but also importing resources (fuel, immigrants, money in the form of debt) to keep our economy stable – this may become unsustainable. If we are unable to source those resources – war, pandemic, depleting resources to name a few reasons – then our country as a system starts to become unsustainable.

There are ways to deal with this input and output of resources from a system’s boundaries, however. Considering that the resources in are finite (they’re used faster than they’re made), we could reduce the amount of resources we need to use to make the input arrow smaller to match the output arrow.

This is where some other concepts come into play: efficiency – a more efficient process uses less resources; reduce, reuse, recycle – using less non-renewable resources (recycling is a way to make a resource renewable essentially); resilience – if a hazard occurs wiping out a whole lot of resources, extra resources are needed just to repair the system, rather than for production; or similarly diversity – making sure all our eggs aren’t in one basket, so we have options if one resource becomes depleted or unavailable.

How far out can our system boundaries go before we need to stop worrying? Well, our ultimate system is the earth including its atmosphere. Draw the boundary around earth’s atmosphere, and that’s where the system ends (we’re not going to consider populating Mars). As long as we’re not using more resources than the earth produces (side note: the sun’s energy is free), then we are living sustainably. Spoiler alert – we’re definitely not.

So why does the term sustainability seem to be used in reference to carbon emissions a lot of the time? Well, think of this system as being the carbon cycle only. Some things use up carbon: trees and plants use carbon to grow and then they lock in the carbon until the tree dies – if the tree decomposes, it releases carbon into the atmosphere – or is burnt (again, releasing carbon to the atmosphere). Because the tree does not produce carbon, the carbon stored inside increases.

But other things will convert carbon fuel into carbon dioxide, taking stored carbon and changing it into carbon gas (carbon dioxide), which releases the carbon into the atmosphere. “Net zero emissions” is when we’re putting say 100 units of carbon into the atmosphere, but we’re also planting enough trees to absorb 100 units of carbon over the same period. Carbon emissions are particularly important for the earth’s ecosystem, because if we’re putting more carbon into the atmosphere (cars) than we’re removing (trees), then the earth will cope by adjusting the climate to deal with the higher levels of carbon in the atmosphere – this is climate change.

New Zealand mostly uses renewable resources to produce electricity – wind, geothermal and hydro are all considered to be renewable resources – which makes electric vehicles a viable option. Electric vehicles use a renewable resource for input (energy), but also do not emit carbon as a waste product, like fuel-powered vehicles do.

Sustainability can get complicated when we’re talking about environmental effects. That’s because we’re referring to an eco-system, or a system that needs to be able to sustain itself without negatively impacting the environment around it (and therefore affecting its adjacent system).

A system that produces toxic waste, is not sustainable because it’s releasing toxins into an adjacent eco-system which may be depleting that systems resources. When we dig up a riverbank and sediment erodes into a stream, the sediment clogs up the stream, killing plants which are both eaten and which produce oxygen, therefore killing fish – unsustainable, because things are dying (depleting). Systems rely on adjacent systems to be able to sustain themselves, all the way up to the outer edges of the earth’s atmosphere.

An industry that loses more workers (emigration, retirement, physical and mental illness) than it gains, is unsustainable. We need to make sure enough people are being trained up and the work they’re doing is interesting and safe enough to keep them in the industry, in order to sustain that industry.

We need to ensure the quality of what we’re building is good enough that it doesn’t need replacing too soon or is destroyed by a natural hazard. We need to make sure we’re not producing excess waste that ends up in landfill, which is an unsustainable practice, because eventually we run out of space. We need to innovate processes that don’t use as much finite resources.

Consider how much cut to waste and importing fill is required – not only because it’s an expensive way to do earthworks, but because disposal of the cut to waste uses up space (which is also a finite resource) and then requires aggregate (finite resource) to be imported, where the cartage burns fuel (finite resource) and emits carbon (climate change).

Hopefully you now have a better understanding of why sustainability is such an important word, how systems work, what makes a resource finite, why efficiency, diversity and resilience are important, how adverse environmental effects can impact systems, how systems can adjust themselves to create a balance. And crucially, how systems are interrelated and impacts to one system affect the balance of other systems.

The earth is the ultimate system and will adjust accordingly to ensure its survival – with or without us. That’s why sustainability matters.