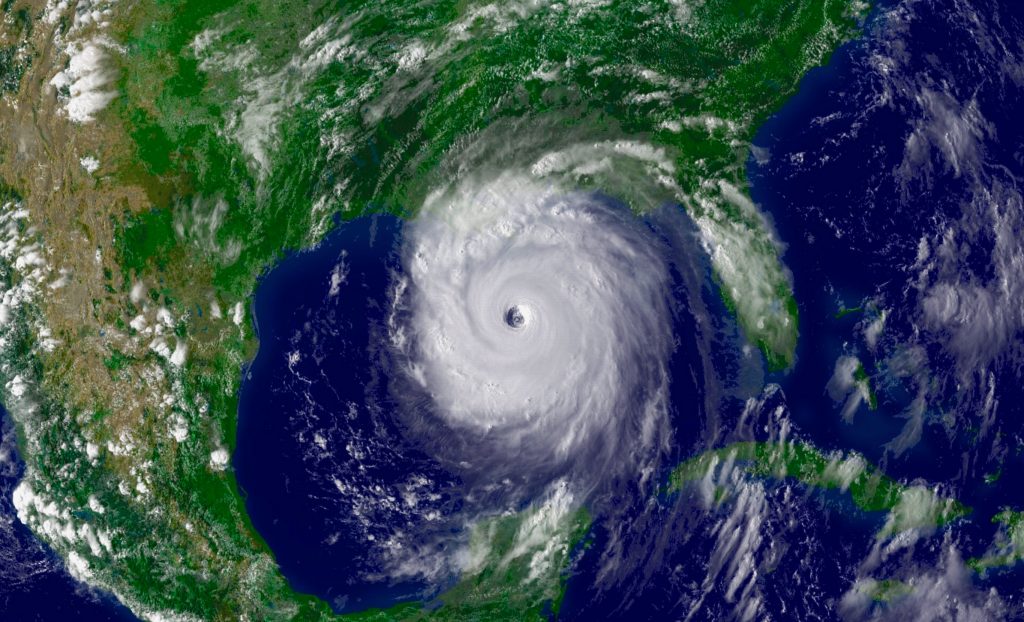

Cyclone Gabrielle has highlighted the challenges New Zealand faces grappling with the impacts of climate change, including sea level rise, changing weather intensity and storm surges. It will be both international and local insights and intelligence that guide our approach.

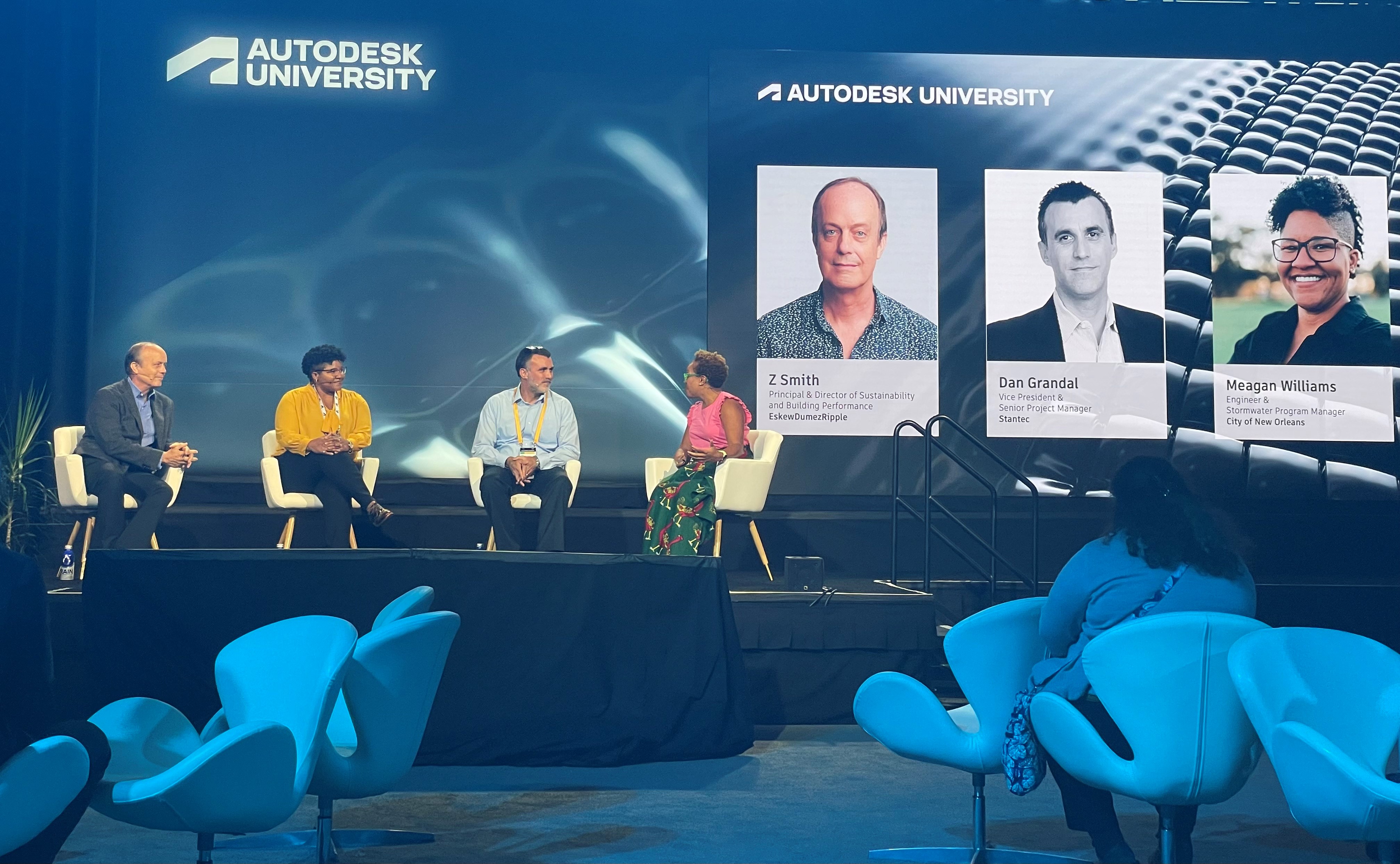

At the 2022 Autodesk University Conference in New Orleans, which the author attended, a panel discussed the city’s triple layered response (federal, city and community) to increasing sea level rise and storm intensity:

- The US federal government has invested significantly in surge protection mechanisms in the Gulf of Mexico to seek to compensate for the loss of marshlands that offered natural protections to the area.

- At a city level, New Orleans, as well as investing in significant pumping capability, has been revisiting its approach and adopting system more akin to a natural catchment system using green spaces.

- At a local level, one social housing development sought to take that concept of resilience further, developing a building with great water and energy resilience.

On the Autodesk University panel was City of New Orleans Engineer and Stormwater Program Manager Meagan Williams, whose stormwater responses were the result of her experiences as a 16 year old being affected by Hurricane Katrina.

Hurricane Katrina was a destructive Category 5 Atlantic hurricane in late August 2005 that caused over 1,800 fatalities and US$125 billion in damage – the costliest tropical cyclone on record at the time as well as the fourth-most intense Atlantic hurricane on record to make landfall in mainland United States of America.

Williams’ experiences prompted her to study in her chosen field of practice. It also meant she knew to sit with the people and listen to their experiences of the change and of the pinch points they experienced before designing local stormwater attenuation solutions.

Federal level engineered responses

New Orleans is protected from storm surge by a system of federally funded levees known as the Hurricane Damage Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS). The levee system was rebuilt by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) in the years following Hurricane Katrina.

The 1.8 mile-long, $1.3 billion Lake Borgne Storm Surge Barrier is the largest civil-works, design-build construction project in the history of the USACE.

After its construction in 2013, the Corps transferred operation and maintenance responsibilities to the Flood Protection Authority – East.

The Surge Barrier is a complex system made of concrete and steel that is located at the intersection of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW) and the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO). It includes a monolithic flood barrier of 1,071 “soldier” pilings at 140 feet in length, 26 feet above sea level, and 240 feet in length “battered” piles extending to 200 feet underground. Adjoined to the barrier wall is a 150-foot-wide sector gate, a bypass barge gate, and a 56-foot-wide vertical lift gate.

The engineering intervention is significant but even it is designed only to prevent a 100-year storm surge from inundating the New Orleans metropolitan area.

In addition, attempts are made to have the natural systems including the power of the Mississippi River to itself build coastal wetlands again have some effect. Ironically manmade interventions through channelisation had diminished the power of these natural systems to regenerate.

City stormwater attenuation informed by resident experiences

The City of New Orleans had historically sought to control and manage stormwater using piped systems and pump stations, but more recently has sought to “channel and coax” floodwaters and have them “sit for a while” using large stormwater attenuation infrastructure constructed under greenways and large road reserves that characterise parts of the city.

New Orleans is now more susceptible than ever before to hurricanes because the protection traditionally offered by the natural marshlands is being eroded.

There is less naturally occurring sediment deposited in coastal marshlands areas due to the channelised course of the Mississippi river (the levees themselves a historical flood protection mechanism) and up-river dams.

The protective marshlands are also reported to be impacted by seawater incursion exacerbated by oil and gas pipelines and exploration and water based transport systems through canals cut across the marshlands.

Coupled with the loss of land from sea level rise generally, the future of the marshlands is concerning both ecologically, and in terms of its protective effects on human settlement in the state.

There are many displaced communities, including those indigenous populations resettled in marshland communities as part of historical resettlement initiatives where newer urban form “took the higher ground” that are having to rethink where they live.

Localised building response

At a local level in New Orleans residents within the city are susceptible to utility outages and one team in New Orleans developing social housing sought to also address storm resilience at a building level.

They were collaborating online using Autodesk software solutions and trialled the effects of substituting more sustainable building solutions both in terms of embodied carbon and in terms of energy and stormwater management, without compromising the functionality and aesthetics of the building. Those design changes included solar capability.

Local relationships enabled them to access surplus retired electric vehicle batteries from Toyota and a local utility excited by the possibility of stand-alone energy resilience, bridged the funding gap to enable the team to implement their solutions. That enabled designers and constructors to trial a number of alternatives including a self-sufficient building solution involving roof-mounted solar arrays.

The value of the alternative approach they took was demonstrated when subsequent power outages during Hurricane Ida took out the local networks. The buildings residents were the only city dwellers in a five block radius still enjoying the benefits of power and able to continue with their daily lives within the complex.

What can a coastal nation like New Zealand learn from the experience of New Orleans?

In a long thin largely coastal country, with a young geological form, our built environment and infrastructure has tended to be concentrated in coastal and riverine areas. Although pragmatic, that is a problem for us going forward.

We are already grappling with where to build and what represents an appropriate response to the risks we face.

We will also need to consider whether some existing areas of settlement can, or should, continue to be protected, with managed retreat the subject of third bill in the resource management reform package expected shortly.

There’s an increasing recognition that we have neither the resources nor the workforce to “engineer” our way out of the magnitude of all the problems that face us in the same way that New Orleans has with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers USACE (being a workforce able to be deployed at scale on problems of this magnitude and even then with some limitations) and so location becomes critical.

Just as is the case in Louisiana, the role of naturally occurring wetlands and marshlands has until quite recently been poorly understood. With increasing focus on their role in both freshwater management systems and the carbon sequestration function they perform, they are also important in our response.

We too can benefit from a multi levelled approach to responding, including at a building level. The conversations around the type of structures and approaches to building that increase our resilience are already happening.

Future Stormwater management and its relationship with the built environment is complex and highly topical, with the variety of catchments even giving rise to suggestions from some that our three waters reform should instead be revised to address only potable and wastewater.

The other factor to bear in mind is that the effects are felt unevenly, both socio-economically and culturally. NIMBYism (not in my backyard) can push social and lower value housing to suboptimal areas where the environment is less suitable for housing and the design decisions made become extremely important.

There may be a cultural cost too that is a legacy of historical settlement patterns.

It is well established that Māori pa and Urupa often sited coastally and on rivers for water accessibility are doubly impacted by sea level rise and storm surges. As well as the physical damage, there may be a severing of connection to place and tupuna that lies at the heart of personal identity and wellbeing, with the Whakatauki, Ko au te whenua, te whenua ko au (I am the land and the land is me), speaking to the fundamental nature of those connections.

A key insight is the need to think about working with nature, rather than always trying to surmount it.

Perhaps we all need to look to history and a Pūrākau (myth) dating back to Anglo Saxon times. There is the story of Cannute or Kanute the Anglo Saxon king who reportedly commanded the sea not to advance beyond his throne placed in the path of the tide. Recent historical analysis suggests that, rather than the gesture being a manifestation of arrogance borne of his status, it was the exact opposite. He was instead demonstrating that no one, regardless of their status, can control the tides.

A salutary message perhaps for us all.

Adrienne Miller

Chief Executive

Urban Development Institute of New Zealand