Thanks largely to decades of underinvestment, New Zealand’s government debt is actually quite low, but when faced with a $100 billion infrastructure deficit, The Kaka Editor Bernard Hickey suggests borrowing more could be the fastest and cheapest solution

Finance Minister Nicola Willis has again characterised the Government’s finances as too fragile to borrow in its own right to solve Aotearoa-NZ’s infrastructure deficits.

She also again compared the Government’s budget to a household budget, saying spending cuts needed to be found to ‘balance the books’ and that she was afraid of losing the confidence of financial markets when the ‘rainy day’ came for borrowing.

But the ‘grown-ups’ in financial markets and in ratings agencies are saying the exact opposite. S&P Global Director of Sovereign and Public Finance Ratings, Anthony Walker, tells me the Crown’s AAA rating was not fragile and the Crown had 30% of GDP ($120 billion) of borrowing capacity before it would be downgraded.

He says the Crown using its balance sheet to borrow from fund managers to fix infrastructure deficits would be the fastest and cheapest way to do it. His comments came after record-high demand for a 30-year bond issued by the Treasury’s Debt Management Office at just one basis point above secondary market rates.

Willis describes the Budget inherited from the Labour Government as in an “unsustainable fiscal situation”.

“We are a small exposed trading economy so we are far more vulnerable to shocks and being able getting access to cash than those really large economies,” she says.

The implication is that the Government, therefore, cannot afford and does not want to use its balance sheet to borrow on its own accord to invest in infrastructure. She repeats comments made previously by herself and Infrastructure Minister Chris Bishop that the Government would create a National Infrastructure Agency that arranged city and regional deals, whereby councils would borrow from private investors and arrange Public-Private-Partnerships, rather than the Government borrowing directly through the Crown’s balance sheet.

“We can afford to deliver infrastructure and there’s a few things we’re going to do that are going to make our dollars go further.

“One that’s important is we’re going to have a much faster approach to consenting which will reduce the cost of projects.

“The other is we’re going to have new forms of funding and financing which will see us working with iwi and other private-sector funders,” Willis says.

‘Stop mucking around. There’s plenty of borrowing headroom’

However, S&P Global’s Head of Government ratings, Anthony Walker, told me in an interview in my When The Facts Change weekly podcast via The Spinoff that the nation’s finances were not fragile and there was the equivalent of 30% of GDP ($120 billion) borrowing headroom left before any danger of a credit rating downgrade.

Walker says there is immense investor demand both globally and locally to lend tens of billions to the central Government in vanilla bonds to repair and extend infrastructure such as water and roads. That would be the cheapest and fastest way for Aotearoa-NZ to address its $100 billion infrastructure deficit, which the Infrastructure Commission has indicated could grow over $200 billion in coming years.

Emphasising the actual strength of the nation’s finances and the demand for very long-term Government bonds, Treasury successfully borrowed $4 billion through a new 30-year syndicated bond issue yesterday with a record-high $19 billion worth of bids — a coverage ratio of almost five times. The yield achieved of 5.09% was just one basis point over secondary market price of the closest maturity May 2051 bond.

Here’s BNZ’s Senior Interest Rate Strategist Stuart Ritson commenting on how the success of the bond auction yesterday had actually dragged down bond yields in the secondary markets:

“The 2054 syndication saw strong demand with the orderbook at final guidance exceeding NZ$19 billion. New Zealand Debt Management issued NZ$4 billion which was previously indicated as the volume cap for the transaction. The 2054 was issued at a spread of +1bp to the May-2051 bond which was towards the tighter end of initial price guidance. The strong investor demand will support market sentiment given the heavy funding requirements ahead.” BNZ’s Stuart Ritson.

So what is National-ACT-NZ First doing instead?

Instead of using its balance sheet to spread the cost of infrastructure crucial to solving our housing, climate and poverty issues, the National-ACT-NZ First Government is pushing ahead with a piecemeal approach. It plans to encourages councils to fund the investment in dribs and drabs through a series of ‘city deals’ that cobble together council bond issues with public-private-partnerships, which are smaller and more complicated than the failed Transmission Gully deal engineered in the last days of the previous National Government.

Walker says bond investors would much prefer the Crown used its own AAA-rated balance sheet to borrow the money, which would also be much cheaper for the Crown. Fund managers prefer more liquid bonds with the strongest guarantor, which will always be the Crown because it has the power to tax incomes and spending. Councils can only tax property.

‘The Crown is not fragile and council borrowing is at its limits’

I asked him if New Zealand’s fiscal position was fragile and what bond investors would prefer: sovereign debt or local and bespoke bonds.

“It’s (New Zealand sovereign debt) generally very, very low risk. From our point of view, AA-plus foreign currency, AAA local. We’d like to look at the foreign currency because it’s comparable with other countries. It’s the second highest. So we have something like 10 AAAs in the world out of 140 sovereigns we rate. So it’s the second notch out of 20 on the scale. It’s extremely low risk. Bond investors know that. They like the rule of law,” Walker says.

“As much as we hear, oh, there’s a divide between Labour and the National party, in the New Zealand context, yes there is, but in the global context, politically, those two parties are aligned on 90 % of what they’re doing.

“You don’t have the fragmented systems in Europe or America. Say Europe, you have six parties coming together to form government. The US, they’re polar opposites. You don’t have that in New Zealand. Investors actually like that. They know they come to New Zealand, they’re going to get well disclosed, transparent system, who’s going to do the right thing. They don’t have to worry about those type of things.

“And from a borrowing perspective if they were to borrow at the sovereign level. Net debt on our scale is around 30% of GDP. For us to lower the debt assessment, it needs to double. If you think about that, an extra 30 % of net debt, that’s $120 billion of extra debt they need to do just for us to lower the debt assessment. So there is a fair bit of headroom there from the sovereign’s balance sheet,” Walker says.

I asked him if financial market pricing and yesterday’s bond auction demand also showed confidence.

“If it was an issue, we wouldn’t have a AA plus rating. We wouldn’t have a stable outlook. I’m not saying go out and borrow 120 billion. I’m just saying that New Zealand sovereign has headroom. It has headroom on its balance sheet to spend money,” Walker says.

“But from a fragile point of view, you don’t have investment grade ratings that are fragile. If they’re fragile, they’re not investment grade. They’re 10 or 15 notches below where New Zealand is right now.”

I also asked Walker about the cost of plain sovereign borrowing versus a series of bespoke and small local ‘city deal’ or regional deal bond issues linked to PPPs.

“The cheapest way for ratepayers and taxpayers of residents is the sovereign. It has the biggest balance sheet. Water at $10 billion or $15 billion is a big number for councils. For the sovereign, it’s quite small,” he says.

“But you’re talking about an economy of $400 billion, roughly. If it’s (the borrowing) $20 billion, that’s 5% (of GDP). New Zealand as sovereign is the biggest borrower, the cheapest borrower in the country. It has the power to do it. Local councils being fragmented, it’s harder to get the kind of demand there. And again, local councils will pay a premium.

“At the same rating level as the sovereign, they will not get the same price. It’s usually around 80 basis points 1% (100 basis points) higher on very similar terms.

“So from a New Zealand rate payer or taxpayer advantage, the cheapest way of doing it is the sovereign. It has the mass, it has the size. But again, it comes down to whether they want to do it, whether local government act, and the responsibility split. Those things need to be looked at. And whether that is a quick solution, it may not be,” Walker says.

I also asked why local and international fund managers prefer sovereign bonds to local bonds. He points to the creation of the Local Government Funding Agency (LGFA) to try to aggregate supply, but even then, fund managers want sovereign debt.

“Generally investors will like sovereign because it’s, yes, low yielding, pays less interest, but it’s safe because they know they’re gonna get the money back. But they also look at liquidity. Liquidity is extremely important here. So Horowhenua and South Taranaki for example — we can use any regional council, we work on 25 of them — They borrow through the LGFA to get the aggregate demand up,” Walker says.

“So if you’ve got a council issuing $10 million here and there, an investor is going to say, well, if I buy that bond, I can’t sell it. I have to hold it until maturity. There might be one buyer. I’m going to take a premium because I’ll never be able to sell this bond for 10 years.

“LGFA is doing a billion, one and a half billion a year. They’re actually getting everyone’s money together and issuing it. It means liquidity is much, much better through the LGFA than local council. And investors are willing to buy it because they know if something changes, they change their mandate, they change their rules, they can actually sell it to somebody else and get their money back.

“They don’t have to hold it for 5, 7, 10 years until maturity. But liquidity is extremely important. We see that. Look at Europe. We have governments in Europe which are in the triple B -minus, so I can write at the bottom of this grade. Their interest costs are much lower than New Zealand because of the economic situation and the proximity to European investors. They know what Italy is doing. They’re in bed when New Zealand’s awake and they charge premiums for this other thing. And as I said, New Zealand sovereign name is much bigger. They’re much more comfortable holding that.”

But the biggest problem at the moment is the high-growth councils such as Auckland, Hamilton, Tauranga, Wellington, Christchurch and Queenstown can’t borrow more in their own right, given their lack of access to revenue from GST or income tax, as councils in other parts of the world have.

Three Waters was Labour’s attempt to create new off-balance-sheet vehicles that could borrow in their own right with the power to charge for water, which would allow water infrastructure investors to get around the current council debt limits. But National’s repeal of Three Waters and its reluctance to fill the gap with Crown capital or shared taxes has blocked off that path.

15 council ratings are under review for downgrades because of the funding vacuum that has opened up after the demise of Three Waters.

“New Zealand from a central government point of view has very, very strong fiscal outcomes. And that divide (with councils) is actually widening at the moment,” says Walker.

“New Zealand councils account for 10% of the country’s debt. The sovereign accounts for 90%. But when it comes to infrastructure spending, New Zealand councils are predominantly responsible for it. In other countries, we do have revenue sharing arrangements, not just through GST.”

‘And we don’t accept the idea the Crown won’t guarantee these CCOs’

ACT has proposed the Government share GST with councils, but National has only said it will consider the idea. National is still insisting that any Crown Controlled Organisations (CCO) set up voluntarily would not have a Crown guarantee.

Walker poured cold water on the idea ratings agencies and bond investors would accept and buy CCO or council bonds without guarantees.

“There is a potential that these CCOs do get established. We do have to look at them individually. If Watercare was just put into a Watercare entity was 100 % controlled and owned by Auckland, we’d put it back on (Council) balance sheet. Because if something goes wrong at Watercare, investors can’t get the assets under the laws. So what do investors do? The same investor funding Watercare is funding Auckland, and they’re funding Wellington.

“And if Auckland doesn’t bail out Watercare, well investors are not going to start funding Auckland. They’re not going to give them money to start funding the new football stadium or new roads. So there’s a contagion risk across the entire sector when that happens. So there’s always (political) incentives (to bail out CCOs), particularly water.

“And we’ve seen it in New South Wales, for example, where they tried to do some of this stuff and it went pear shaped and ministers started losing their jobs. When governments are losing their jobs, they spend money. We’ve seen that across the world. It’s easier to pay somebody else’s money than lose your job,” Walker says.

Just in case it wasn’t clear, that comment was effectively Standard and Poor’s — a key ‘grown-up’ of the financial world — telling the Government that it and bond investors simply won’t accept the idea of the Government not guaranteeing these entities.

So we’re back at square one.

So where does this leave us all? In essence:

- Three Waters was the solution the ratings agencies and bond investors might have accepted, but that’s now gone;

- Bond investors and ratings agencies would much prefer the Government just got on with it and either borrowed the money directly via the Crown’s balance sheet and paid to build the infrastructure itself, or started sharing tax revenues with councils; and,

- National-ACT-NZ First are unwilling to borrow on the Crown’s balance sheet or share tax revenues with councils or guarantee CCO debt.

That means there remains a painfully large gap and missed opportunity between the fund managers wanting to lend tens of billions of dollars to the Government to fix our infrastructure issues, and the Government, which still wants to avoid extra borrowing by instead using a complicated hodge-podge of bespoke little bond issues it hopes it can get away without guaranteeing.

The end result?

- the water networks don’t get built or repaired, which blocks the rapid expansion of housing supply to cope with population growth and to try to restore affordability for renters and buyers;

- strong population growth from migration of workers on temporary visas continues, which represses wage growth, pumps up rent growth and further inflates demand for now-limited zoned residential land with water networks — a combination that drives up land and rental property values; and,

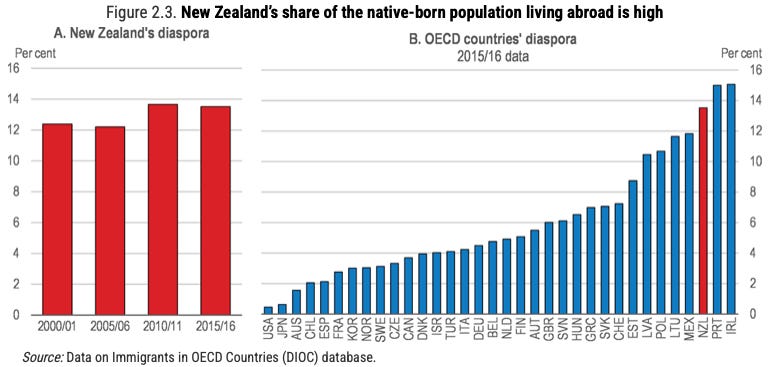

- more New Zealanders give up on ever being able to start or keep a family in an affordable and secure home they own or rent, and leave to live overseas permanently with the other one million New Zealand-born diaspora — nearly 14% of the population and the third largest in the OECD as a share of our total population. Australia’s diaspora is less than 2% of its population.

How can this be politically sustainable?

Ratepayers and taxpayers who own residential property or properties know their financial futures depend on growing their capital gains from residential land as fast as possible, which requires as much disposable income as possible for as much leverage as possible. Only relying on savings from actual work or businesses is pointless when competing against families able to leverage their share of the $1 trillion of equity in their own home or homes. Working for a living or building a (non-residential property) business is a mug’s game.

The following are the key conditions for median voters and voting ratepayers to keep growing those tax-free gains as fast as possible:

- infrastructure investment is strangled to limit the supply of land available for housing, which in turn inflates the value of the existing land able to be lived on;

- migration and population growth needs to stay high to keep upward pressure on rents and land prices;

- disposable income after rates and income taxes need to be as high as possible to be able to borrow as much as possible from banks to bid for and buy the most residential land;

- capital gains and land must remain tax free; and,

- mortgage rates must be as low as possible, which means Government debt and council debt should be as low as possible, which works in tandem with the first condition of limited infrastructure investment.

This explains why governments and councils from both sides of politics are so reluctant to use Government debt to borrow to build the infrastructure, or to share tax revenues with councils or tax land or capital gains. Increasing debt increases mortgage rates. Taxing capital gains or land reduces or destroys the ability for fast rises in home equity. Higher income taxes or rates reduces the disposable income able to leveraged into a home or more homes to rent out.

First published at: Govt’s Budget ‘just like a household,’ says Willis (substack.com)