Did the government’s electric vehicle programme go far enough in addressing New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions?

The man behind the authoritative Electric Vehicle Policy: New Zealand in a Comparative Context report doesn’t think so.

“It’s good to see the government taking some action – it’s certainly an area where New Zealand can improve,” says Waikato University Professor of Law Barry Barton, who co-authored the report with Bremen University Law Lecturer Peter Schütte.

“They have done many of the things that international literature says are desirable but they haven’t done the things that international evidence shows are essential, so it’s not entirely clear how successful the programme will be.”

First and foremost, Barton believes the government should release an analysis of its figures on its target of 64,000 electric vehicles (EVs) and what effect that will have on greenhouse gas emissions.

“It would be wonderful to know about the efficacy of the policy actions they’ve taken to achieve that target – are the two actually related at all and will those measures reach that target?” he questions. “They may very well do but it’s unclear.” He says the same about whether the policy actions will produce the change that will reach the target.

The government should also have introduced other measures and not necessarily “feebates”, which provide a price benefit or charge on the basis of the entire light motor vehicle fleet’s CO2 emissions upon initial registration.

“I’m not a campaigner for feebates but price is an issue and the government hasn’t done much on that,” Barton maintains. “They’ve provided a subsidy in relation to the road user charges but that doesn’t go far enough.”

It’s also spread out over time and there’s “plenty of evidence” that shows that approach doesn’t particularly influence people’s choices. “Immediate incentives are much more effective – there’s sound basis for that in the literature,” he explains.

“There’s also an equity issue – some people have the capital to deploy to reduce costs over time but others don’t and we have to think of them as well if we want to increase electric vehicle uptake.”

The other aspect that concerns Barton is the fuel efficiency of the vehicle fleet as a whole. “Again feebates tackle that, but if we’re not going to introduce them you really wonder whether it’s worth putting a lot of effort into electric vehicles at all.”

Nor is he certain that the government will reach its target of 64,000 given that the current EV fleet is only about 1,000 vehicles. “Electric vehicles haven’t yet reached a mass market – many of those that have been bought are held by aficionados, but there aren’t many who dedicated enough to spend an extra $10-20,000 dollars on purchasing an electric vehicle.”

In addition, Barton suspects many EVs will have been bought by organisations such as the power and petrol companies for commercial reasons. “Mighty River, for example, has acquired several electric vehicles; I think mainly to figure out how this might work as a business opportunity.”

Greenhouse gases

Ultimately, he says the answer to the question of why EVs are important is in relation to greenhouse gas emissions. “Even 64,000 cars against the current fleet of 3.5 million vehicles is a very small step forward,” Barton notes.

“A colleague has done a back-of-the-envelope calculation that suggests if we reach that target then the NZ emissions from transport alone would come down maybe one per cent.”

That’s where EVs have to be accompanied by other measures, he insists. “The government’s has to implement similar programmes with relation to biodiesel, hydrogen, active transport like cycling and walking, and public transport.”

Much also depends on the overall vehicle market, which sees heavy diesel-powered vehicles producing about 45 per cent of the total greenhouse gas emissions, with little prospect of many of them going electric.

“There are huge possibilities to reduce greenhouse gas emissions without affecting the nature of the vehicle fleet and restricting people’s choices,” Barton argues. “For example, the government could put in place mechanisms such as the feebate that will help affect the choices people make.”

Another potential stumbling block is the charging infrastructure, though he notes that the private sector is ahead of the market with the power companies and others such as Charge Net providing “reasonable coverage” for what is, after all, a mere 1,000 EVs.

Infrastructure is important in encouraging people to switch to electric vehicles, Barton asserts. “For example, Oregon has quite a high uptake of electric vehicles, not because of subsidies but because it has a very good charging infrastructure.”

Clearly the government’s measures fall short of those outlined in Barton and Schütte’s paper, which argued that a “bold approach” is needed given the increasing attention electric vehicles (EVs) are attracting worldwide.

Big benefits

- They noted that EVs offer several public benefits when compared to internal combustion engines, specifically regarding:

- greenhouse gas emissions

- energy efficiency

- energy security

- air pollution and noise.

“This is particularly so in New Zealand where approximately 80 per cent of electricity is generated from renewable resources,” they observe, adding that transport is a large and rapidly-growing contributor to New Zealand’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The main barriers to EV uptake are:

- substantially higher capital cost in comparison with internal combustion vehicles (ICVs), even allowing for reductions that are likely to occur

- shorter driving ranges combined with recharge times – especially in terms of public perception

- the need for a better-developed charging infrastructure

- the lack of policy measures that properly measure the adverse effects of ICVs to provide fair comparison with EVs.

Any programme to encourage EVs in New Zealand needs to be part of an overall mobility strategy that takes an ‘avoid, shift, improve’ approach to transport – for example, in producing improvements in the whole vehicle fleet.

Public policy is the main driver for the uptake of EVs, the report’s authors believe, insisting that non-fiscal measures such as parking and lane privileges and the encouragement of charging infrastructure are “likely to be useful”.

However, in the face of high EV prices and the absence of fuel efficiency measures the real effect of such non-fiscal measures is doubtful. “On the other hand, the development of a charging infrastructure does not appear to need major government involvement.”

Moreover, their international research shows that uptake of EVs is rare in jurisdictions that do not have significant fiscal incentives for the price support of EV purchases.

A further handicap is the fact that New Zealand and Australia are distinctive internationally in not regulating vehicle fuel efficiency in any way beyond a labelling requirement.

Fuel first

Very few countries, if any, are trying to promote EVs without fuel efficiency measures, the report observes, and it may not be possible to promote them without fuel efficiency requirements.

There is ample evidence that a general price on carbon such as an effective Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), gives a price signal for using hydrocarbon fuel that is necessary, but not sufficient on its own, to induce significant change.

The solution, the authors conclude, is a suite of EV policy measures that have credibility and a proven record of success internationally and are suitable for New Zealand conditions.

First and foremost is a “feebate” scheme that would apply to the entire light motor vehicle fleet on initial registration and would provide a price benefit or charge on the basis of the vehicle’s CO2 emissions.

The size of benefit or charge per unit of emissions would be such to provide a real influence on vehicle selection and would be re-set regularly to produce revenue neutrality.

“An effective feebate system would avoid the need to introduce price subsidies for EVs,” the authors maintain. “It would operate as a form of fuel efficiency standard for the benefit of the entire light vehicle fleet.”

The feebate scheme would be accompanied by a campaign to improve public awareness, perceptions, and knowledge of EVs as an option; carefully directed at different audiences and based on perception and behaviour research.

A public charging infrastructure should also be encouraged, together with standards for charger plugs and communication protocols, and powers for road-controlling authorities to manage street activity.

In addition, legislation would be necessary to provide clarity and permanence, improve the investment climate, remove barriers, and clarify uncertain points.

These measures should be combined with price pressure on the use of hydrocarbon fuels through the ETS at a level high enough to bring about changes in vehicle use.

“Other barriers that have already been identified such as the fringe benefit tax will doubtless be followed by more challenges, not the least of which is the development and implementation of a method for EV users to contribute to the maintenance and development of the road network,” the authors conclude.

Charging ahead to a greener future

An electric vehicle charging infrastructure company that was incorporated just 12 months ago plans to build 100 charging stations within four years.

Charge Net NZ began physical installs in October last year and has completed some 18 to date, overcoming several potential problems in the process.

“Sites are most attractive where there are public facilities nearby such as toilets, coffee shops or entertainment areas and with available power supply as close as possible,” explains Charge Net NZ COO Nick Smith.

“Often the most suitable sites are owned by councils or leased to businesses, and partnerships with line companies and retail chains have made this easier to navigate site agreements.”

A single car parking space with an additional space on the verge/footpath/plated area about the size of a phone box is all that is required as a minimum for an electric vehicle (EV) charging station. “Populations of around 80,000 people per station are currently viable,” Smith adds. “For instance, Christchurch will have about four units spread around the city.”

The rapid rollout is spurred by the fact that the majority of electric vehicle (EV) charging happens overnight in people’s garages, but a six-hour wait simply isn’t practical when drivers reach the 120km limit of most EV batteries.

“We are building a nation-wide network of fast DC chargers that let any EV owner quickly fill their “tank”, typically in 10-25 minutes,” Smith explains. “Free from the constraints imposed by the hazardous nature of traditional fossil-based transport fuels, EV charging stations can be placed in much more convenient locations like shopping malls and supermarkets where drivers would typically park for at least 20-30 minutes anyway.”

As the name suggests, a fast DC charger is a much larger version of the built-in, on board charger that converts the AC power from the grid into DC power for the car’s battery. “Fast chargers convert high power 3-phase AC into very powerful DC current, dramatically reducing the charge time – usually to less than 25 minutes” Smith notes.

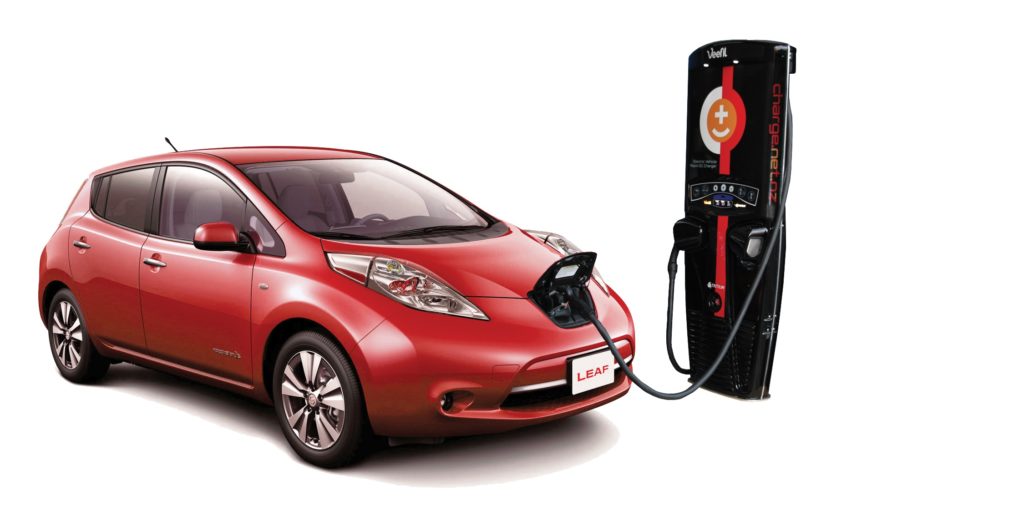

All Charge Net’s chargers support the CHAdeMO standard used by Japanese vehicles like the Nissan Leaf as well as the American Type 1 CCS charging used on the BMW i3. “The Tesla Model S can be charged from the CHAdeMO outlet using an adapter,” Smith adds.

A credit card pre-pay charging system supported by cloud-based technology lets the company’s 300 registered members use a key fob or smart phone app to charge their vehicles using energy supplied by Ecotricity, a zero-carbon certified electricity provider.

Generally speaking only population centres and sites on the main highway routes will have fast charging in the medium-term. “Currently we are targeting 80 kilometres between charging stations in order to enable road trips by an entry level electric vehicle,” Smith says. “As electric vehicle uptake increases then the smaller location may become viable in the future.

It will take approximately four years for Charge Net to roll out the first 100 units, but more may already be required by the time the initial rollout is complete if electric vehicle uptake is faster than anticipated. “Realistically, we’re looking at least 10 years before mass vehicle uptake will reach the point where they challenge fossil fuel vehicles.”

This target would be reached much quicker if the government introduced suitable incentives to spur electric vehicle uptake, Smith feels. “Tax-based incentives directed at fleet and business owners may spur initial uptake and open up the local second hand market shortly thereafter.”

Feebates are another solution of zero cost to government, he adds, but these were ruled out in the government’s recent electric vehicle promotion package.

“Subsidies such as they enjoy in California or ‘fair taxation’ systems like those in Norway exist in other countries but our government is firmly opposed to subsidies and believes that private enterprise will lead the way, so uptake will inevitably take longer,” Smith admits.

Charge Net NZ’s achievements to date were recognised with the recent Z Energy Transport Award, which impressed the judges as “An inspiring and enthusiastic project that has excellent potential.

The timing is well pitched and the accessible and innovative technology is very customer-focused. An admirable display of forward thinking and support for low-carbon transport systems.”

Electric vehicles in brief

There are three main types of electric vehicles:

- Battery electric vehicle (BEV) – pure electric vehicles such as the Nissan Leaf and various Tesla models don’t have a conventional petrol or diesel engine, relying solely on batteries charged from a power point

- Plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV) – the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV is one of four PHEVs currently available in New Zealand that can run on petrol or diesel in the traditional sense (like a hybrid), but also can be plugged into a power point to recharge. PHEVs can run on battery for a short period (typically less than 100km), then the on-board petrol engine kicks in to charge the battery and keep the car going.

- Hybrid vehicles – traditional hybrids such as the Toyota Prius and Honda Civic have batteries and electric motors but their batteries are charged via a traditional engine. Hybrids don’t recharge via a power point and don’t draw off the national power grid.

This article appeared in the June issue of Asia Pacifc Infrastructure News.