A new report that highlights key lessons for the Victorian government when it comes to affordable housing could apply equally to New Zealand

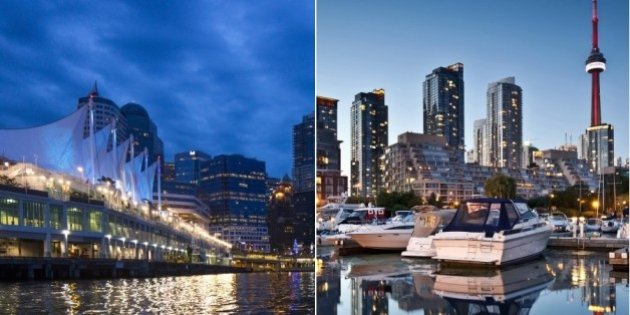

Tap Turners and Game Changers: Lessons for Melbourne, Victoria and Australia from affordable housing systems in Vancouver, Portland and Toronto is the result of Carolyn Whitzman of Melbourne University’s Melbourne School of Design Transforming Housing section visit the three Canadian cities to assess their approaches to affordable housing.

All have big housing affordability problems, caused by a strong economy and 30 years of largely unregulated speculative housing. A lack of federal government involvement has exacerbated these problems.

But these four cities have recently developed very different approaches to housing systems planning, with increasingly divergent results.

Toronto has gone backwards. Vancouver and Portland, though, are reaping the rewards of good metropolitan policy, from which we have drawn 10 lessons for Melbourne:

- Establish a clear and shared definition of “affordable housing”. Enabling its provision should be stated as a goal of planning. This has been done.

- Calculate housing need. We have up-to-date calculations, broken down by singles, couples and other households, as well as income groups, in this report.

- Set housing targets. Ideally, you would want a target of 456,295 new units affordable to households on very low, low and moderate incomes. Both Infrastructure Victoria and the Everybody’s Home campaign have suggested a more attainable ten-year target: 30,000 affordable homes for very low and low-income people over the next decade. This would allow systems and partnerships between state and local government, investors and non-profit and private housing developers to begin to scale up to meet need.

- Set local targets. The state government, which is responsible for metropolitan planning, should be setting local government housing targets, based on infrastructure capacity, and then helping to meet these targets (and improve infrastructure in areas where homes increase). We have developed a simple tool we call HART: Housing Access Rating Tool. It scores every land parcel in Greater Melbourne according to access to services: public transport, schools, bulk-billing health centres, etc.

- Identify available sites. We have mapped over 250 government-owned sites, not including public housing estates, that could accommodate well over 30,000 well-located affordable homes, with a goal of at least 40 per cent available to very low-income households. Aside from leasing government land for a peppercorn rent, which could cut construction costs by up to 30 per cent, a number of other mechanisms could quickly release affordable housing. Launch Housing, the state government and Maribyrnong council recently developed 57 units of modular housing on vacant government land, linked to services for homeless people. The City of Vancouver and the British Columbia provincial government recently scaled up a similar pilot project to 600 dwellings built over six months.

- Create more market rental housing. Vancouver has enabled over 7,000 well-located moderately affordable private rental apartments near transport lines in the past five years, using revenue-neutral mechanisms. Portland developers have almost entirely moved from speculative condominium development to more affordable build-to-rent in recent years.

- Mandate inclusionary zoning. This approach, presently being piloted, could be scaled up to cover all well-located new developments. Portland recently introduced mandatory provision of 20 per cent of new housing developments affordable to low-income households or 10% to very low-income households. If applied in Melbourne, this measure alone could meet the 30,000 target (but not the current 164,000 deficit or 456,295 projected need).

- Dampen speculation at the high end of the market. This would help deal with the oversupply of luxury housing. Taxes on luxury homes, vacant properties and foreign ownership could help fund affordable housing.

- Have one agency to drive these changes. The impact of an agency like the Vancouver Affordable Housing Agency is perhaps the most important lesson. The Victorian government has over a dozen departments and agencies engaged in some aspect of affordable housing delivery. We suggest repurposing the Victorian Planning Authority with an explicit mandate to develop and deliver housing affordability, size diversity and locational targets set by the next state government.

- A systems approach is essential to build capacity. It will take time, coordination and political will for local governments to meet targets, non-profit housing providers to scale up delivery and management of social housing, private developers and investors to take advantage of affordability opportunities, and state government to plan for affordable housing. Eradicating homelessness and delivering affordable housing for all Victorians is possible. But it needs a systems approach.

This is a truncated version of an article by Carolyn Whitzman, Professor of Urban Planning, University of Melbourne; Katrina Raynor, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Transforming Housing Project, University of Melbourne; and Matthew Palmis a Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Transforming Housing Research Network, University of Melbourne, that originally appeared in The Conversation